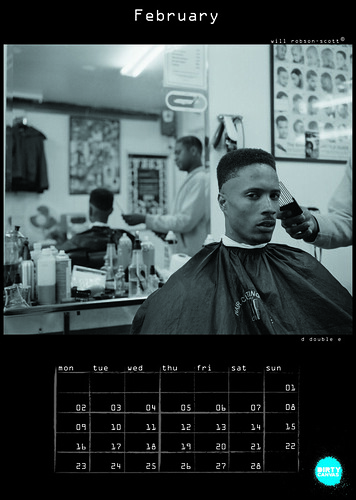

The search term "Big Ben" into Flickr yields 134,706 results. By contrast the term "Crossways Estate," (aka east London's "Three Flats"), yields 23, three of them about maypole dancing at a village fete. It was in this way that I first found

Nico Hogg, aka Nicobobinus' photos.

It was around two years ago, when the first ideas around "Margins Music" began to coalesce that I found great resonance with Nico's photography. Time and time again I would search on Flickr only to find a visual representation of the sounds I'd heard in my head or the environment I'd been inspired by. At first I don't think I clocked it was always Nico's shots I came back to, but then one day

Stuart from Give Up Art, who designed our album artwork and does all the Tempa, Rinse and Applepips art too, emailed me a photo. On the surface it said "No Spitting" but, written in two languages, it also screamed "grime" and "London", while tugging at the respective definitions of those two words.

People talk about glass ceilings in UK culture caused by race and class, but London has glass walls. Throughout this decade I've found myself coming back to the realisation of how insane it is that people so densely geographically located in a city can pass so close without any meaningful sense of understanding of each other. People pass each other without contact, like planes stuck in parallel concentric holding patterns above Heathrow, unable to converse with those just a few hundred feet away from them. On the ground, the glass walls of class and race cause peergroups defined by vocation, education and affluence, forming pockets of self-reinforcing values (in analysis of how the London tube bombers were radicalised, experts point to the participation of training camps, not because the camps particularly gave them extra skills, but because by isolating them from the population, they were able to self-reinforce yet-more extreme viewpoints). "It's a small world," people say, acting surprised at finding commonality with a "stranger" who also happens to be their age, race, class, vocation and live in the same city as them. But is their world only small because the glass walls make it seem so?

Nico Hogg is a man who can cycle through glass walls. For me I have Wookie's remix of Gabrielle to thank for opening the door in the wall, because discovering garage taught me a shared language and showed me I had the appetite for finding common ground in places I didn't belong and in which my peers don't go to. But Nico, he just rides on through. His Flickr account is littered with Google Maps screenshots of east London cycle paths, locations he rides pro-actively into, shattering the glass, to take shots of. And by locations I don't mean Westminster.

I think it's safe to say that Flickr doesn't need any more photos of Big Ben. If you're the 134,707th user to upload a shot of the central London landmark, what incremental value are you really adding as a photographer? But by contrast, as serendipity threw me into Nico's photographs time and time again, it became clear that here was a man doing something, going places and recording areas precious few others were. "Three Flats" (

above) was one of the first ever locations for Rinse FM. Who else has taken a shot of it though? For these reasons, long before I'd found

a Keysound release by Rinse regulars Geeneus, Riko, Wiley and Breeze to use the "No Spitting" image on, I'd begun a long process of interviewing Nico about his shots.

In the first post, Nico explains in general about his approach to photography and his chosen subject, the margins of urban London. In a second post, to follow, I've presented him with his shots, often grouped in themes, and asked him to explain a little more about how he got himself there, why he took it.

Blackdown: So tell me a bit about you as a photographer: how long have you been shooting?

Nico: Years... maybe since I was about 8, but back then it was different – I'd drag a 35mm compact around with me and take photos of anything, anything at all. I was racking up these massive bills for developing reels of film containing, say, 25 wonky pictures of a reservoir on the outskirts of Edinburgh, shot straight into the sun so hardly anything came out properly. My family were going mental. Then I went over to digital when I was 16, got the internet, met other people taking photos and started taking it a bit more seriously... still working on that last point though!

B: what makes you want to pick up a camera? Why did you choose light as your medium?

N: I just wanted something I could pick up and use to express something. I can't play an instrument, I had a brief spell of writing when I was about 15 but didn't feel it was worth going on with, I can draw stick men but no more than that. It seemed like the best thing to go with. It's that easy, more people should do it. It's the days when I want to show people something new that I want to go and shoot most. Sure, in London people can be quick to match up tower blocks with poverty, inner London, but there are towers dotting the skyline in Twickenham, Kingston and Kew Bridge too. If the Brentford Towers were closer to Central London they'd be icons. I can see them on an album cover now, but that's off people's radars looking from the centre of town. Most of all I enjoy taking pictures of the things other people might overlook – try and show people something new, even if it is very ordinary. The internet is good for that, giving a bit of exposure.

B: Do you feel like you are documenting London? Is there also an underlying theme of social comment to your photography?

N: If I am, it's a funny sort of London. When I started I don't think I was doing it consciously, I just went for what took my interest, but as it unfolded it started to look like a documenting of sorts. The social comment aspect is not one I've actively pushed, but I have my own views and they must have leaked into it over time. It's as much a process of coming to my own understanding of London as it is the pictures telling a story.

B: I'm most excited about your coverage of the margins of London - you seem to cover a disproportional amount: east, south, north east, north. Do you find yourself in these areas or seek them out?

N: It's a bit of a mishmash of both. When I started travelling out to areas with the camera I picked on the places I'd spent time in as a young child: inner south London - Walworth, Burgess Park, Peckham. That was a bit of a personal mission, really. I've only got memories to go on from that period as there were few photographs and none of the people involved in my life at that time are in touch anymore. I wanted to try and grasp a sense of how things were at that time and get a better understanding, so I decided one day to just visit, to try and catch the essence of the place, see how it made me feel. I brought the camera to see how a photo would be influenced by that, and I was pleased with the results so I started broadening out to other areas I knew well; I live in north east London and have friends scattered all round that area, so that's where I've tended to wind up.

I find outer London interesting, heh, maybe too interesting. I think looking at the city by dividing it into travelcard zones is a good way of doing it – round the outside the zone 5/6 areas with their own identities separate from London, especially the ones off the tube map: Romford as Essex, London is somewhere 'that way'. Most of these are settled in themselves, in the grander scheme of things. In the middle, Zone 1 looks at itself, in a mirror, a self aggrandising project, while eyeing up zone 2 – inner London - with hungry eyes. Somewhere new to colonise, to the point that it becomes more akin to 'central' London in the classic sense, where there is this huge wealth, the towering office blocks of the Docklands and the penthouses that come with it. But the time has come where they're pretty stable now too – so expensive to live in that they only attract the wealthiest, while the scramble for council housing is so intense that nobody in their right mind gives up a flat once they've got one.

That leaves the middle belt, these 'ordinary' areas, and I think that's where the true London is now – where the 'old' inner city has been pushed out to, that's where the change is happening. And like the old inner areas that were given short shrift and ignored by the arbiters of hot-or-not 15 or 20 years ago, these areas further out now are too often forgotten, for their better and worse attributes. When the people with money to burn arrived in areas like Whitechapel and Bethnal Green they were force-fed words like 'vibrant' and 'diverse', a showcase model of how London came to be the melting pot that it is, but it's these suburban areas that are seeing the process being repeated now: Walthamstow, Woolwich, Barking, Thornton Heath, Edmonton, and it's like nobody is noticing. And it's worth doing so, because sometimes it isn't a pretty sight – friction between old and new communities, sometimes within the new communities, issues of the sort that the BNP jumps on in Barking & Dagenham, does its scaremongering and gets council seats out of it. But there's something worth celebrating in there too – above all, the fact that the diversity of these areas hasn't had a price tag slapped on it yet by estate agents. Yet. And that's why I like to go and see these places as they are now before it happens, because I think eventually it will.

B: In practical terms, how do you get in and out of these sometimes quite serious areas, often in the middle of the night, while carrying a camera?

N: The camera just sits in my bag until I need it. I like to get a good sense an area before I start going around taking pics of it at night – at least one or two daytime visits first, as much to know where I'm going as it is to see whether it's worth a trip at night in the first place. A good knowledge of where the night buses go from helps too. But most of all, knowing exactly where you are and what's round the next corner makes all the difference with how you carry yourself.

B: Many of your photographs are taken after dark. Do you like being out at night? How does it make you feel? How does it make your shots feel?

N: It's my favourite time to do it – the smallest hours and into dawn. There's something about an empty city, being the only person in such a vast, urbanised space that is very special. Even the scent in the air is different, there's that dewy pre-dawn moisture in the air. You hear more in the silence, you see more in the dark, all the senses are heightened, you become so much more aware of your surroundings, I like to see how that affects me. It's made me realise that the chaos of the daytime city can dull your senses from overload, that London can

be two completely different cities. Compare riding a bus at 5pm to sitting on a night bus coming out of the West End at 3am. Even if people are out of their heads and making dicks of themselves, it's a certain trueness you don't get with the hundred impermeable bubbles sitting around you on the way home from work.

B: Lots of your photos of are of signs, defaced signs, details of local identity, key signifiers: tell me about this theme in your photography...

N: I've always enjoyed exploring what counts as a key signifier for an area – a street name, a mural, a building, that signifies a whole wider area, the one thing that everyone will have an understanding of. The 50p building in Croydon. A pub, a kebab shop! A point of agreement in a divided area, or symbols of the fact that an area is divided, tags on signs. But more interesting is when there aren't any. Is it because the idea of defending a local identity by drawing on signs never caught on, or because it's passed beyond that and it's being done some other way. But what? A balance of power between two different groups built on spoken words? I think things like defaced signs are just a 'stage' in the maturity of a local identity, it isn't the ultimate point.

B: Many of your shots are either signs or buildings, but seldom people. I find myself doing this too, but it eliminates the whole side of portrait taking and of the myriad emotional/gender/age/cultural/racial nuances of the human face, leaving the surroundings to imply the culture and people. Do you consciously shoot this way?

N: One day I really want to get into taking portraits of people, but it's just something I've never really tested the water on. In principle I'd like to get more people into my shots, but I instinctively wait until there's nobody in the frame before I shoot – not sure why. But I like to think someone will look at a picture of a properly grotty tower block, look past the emptiness outside and put on hypothetical x-ray specs, and see the hundreds of people inside doing ordinary daily things, but it's up to them to form their own views.

B:

B: To me, much of what makes London fascinating is not just the highs and lows, but their proximity and inseparability. Is this something you see too?

N: Yeah, I see that. It is the rule rather than the exception now, I think. The city is a pressure cooker of a million different causes and interests, slotted into a thousand different sorts of environments. But it isn't completely harmonious, and barriers are going up all the time – not just gated luxury developments, but regenerated council estates that get fortified round the perimeter with massive fences, and a concierge hut at the entrance monitoring all-seeing CCTV. Who are they keeping out? Who are they keeping in? It doesn't matter whether Londoners are willing to tolerate their neighbours or not if the authorities keep putting up things like that, because a new generation is going to become used to living one side or another of a fence.

B: Given London has both rich and poor, What draws you to the less affluent edges of london?

N: I don't find much of interest in the more affluent areas. I grew up on a council estate in Tottenham, so what happened in Muswell Hill or Highgate was of no interest to me as a child, and to a point that's still true now. I like visiting the parts of London that feel like home, where things are actually in the process of happening, the blatant playing out of different views and opinions, rather than places that are trumpeting about what has already happened, where it is done and dusted, mission accomplished – and they tend to be the more affluent areas. There is a voice in those areas, but it's an energy busy keeping things the way they are so you don't see much obvious evidence of its existence. There's very little different

to see in, say, Highgate from one year to the next, so I don't find myself there often.

B: Crossways estate, Broadwater, Stonebridge, Aylesbury - estates being demolished. You seem to have been to pretty much every estate with a reputation in the capital. These are very territorial places, such that people who live there feel very safe to repel or confront locals or outsiders. How does this affect you when you visit?

N: I've never had to deal with any confrontation! I tend to stay low-key when I'm visiting an estate, especially one with a reputation, but when I have ended up talking to people it's always been pretty amiable. At the end of the day, if you don't put up a front to people then 95% of the time they won't put up a front to you, and that's as true on an estate as anywhere else. But if I do see a situation coming from the distance, I will melt off round a corner... practically speaking though I like to get onto an estate early in the day so I can hit the 'tradesmen's button and get into the blocks, and it tends to be a lot quieter then. On a basic level, if I'm visiting an estate I want to respect that space and not rub anyone up the wrong way while I'm there, because I know I'm an outsider. On some estates, though, they must be used to people wandering in and out with cameras – I was visiting one in Poplar a couple of years ago and took a photo of a multilingual council sign of some sort, when a load of kids came up to me. "There's another sign over there!". I thought that was a nice touch.

The second part of this interview, where Nico talks through some of his shots, will be published shortly...